Figure 1. Self-contained documents

Apache CouchDB is one of a new breed of database management systems. This chapter explains why there’s a need for new systems as well as the motivations behind building CouchDB.

As CouchDB developers, we’re naturally very excited to be using CouchDB. In this chapter we’ll share with you the reasons for our enthusiasm. We’ll show you how CouchDB’s schema-free document model is a better fit for common applications, how the built-in query engine is a powerful way to use and process your data, and how CouchDB’s design lends itself to modularization and scalability.

If there’s one word to describe CouchDB, it is relax. It is in the title of this book, it is the byline to CouchDB’s official logo, and when you start CouchDB, you see:

Apache CouchDB has started. Time to relax.

Why is relaxation important? Developer productivity roughly doubled in the last five years. The chief reason for the boost is more powerful tools that are easier to use. Take Ruby on Rails as an example. It is an infinitely complex framework, but it’s easy to get started with. Rails is a success story because of the core design focus on ease of use. This is one reason why CouchDB is relaxing: learning CouchDB and understanding its core concepts should feel natural to most everybody who has been doing any work on the Web. And it is still pretty easy to explain to non-technical people.

Getting out of the way when creative people try to build specialized solutions is in itself a core feature and one thing that CouchDB aims to get right. We found existing tools too cumbersome to work with during development or in production, and decided to focus on making CouchDB easy, even a pleasure, to use. Chapters 3 and 4 will demonstrate the intuitive HTTP-based REST API.

Another area of relaxation for CouchDB users is the production setting. If you have a live running application, CouchDB again goes out of its way to avoid troubling you. Its internal architecture is fault-tolerant, and failures occur in a controlled environment and are dealt with gracefully. Single problems do not cascade through an entire server system but stay isolated in single requests.

CouchDB’s core concepts are simple (yet powerful) and well understood. Operations teams (if you have a team; otherwise, that’s you) do not have to fear random behavior and untraceable errors. If anything should go wrong, you can easily find out what the problem is—but these situations are rare.

CouchDB is also designed to handle varying traffic gracefully. For instance, if a website is experiencing a sudden spike in traffic, CouchDB will generally absorb a lot of concurrent requests without falling over. It may take a little more time for each request, but they all get answered. When the spike is over, CouchDB will work with regular speed again.

The third area of relaxation is growing and shrinking the underlying hardware of your application. This is commonly referred to as scaling. CouchDB enforces a set of limits on the programmer. On first look, CouchDB might seem inflexible, but some features are left out by design for the simple reason that if CouchDB supported them, it would allow a programmer to create applications that couldn’t deal with scaling up or down. We’ll explore the whole matter of scaling CouchDB in Part IV, “Deploying CouchDB”.

In a nutshell: CouchDB doesn’t let you do things that would get you in trouble later on. This sometimes means you’ll have to unlearn best practices you might have picked up in your current or past work. Chapter 24, Recipes contains a list of common tasks and how to solve them in CouchDB.

We believe that CouchDB will drastically change the way you build document-based applications. CouchDB combines an intuitive document storage model with a powerful query engine in a way that’s so simple you’ll probably be tempted to ask, “Why has no one built something like this before?”

Django may be built for the Web, but CouchDB is built of the Web. I’ve never seen software that so completely embraces the philosophies behind HTTP. CouchDB makes Django look old-school in the same way that Django makes ASP look outdated.

—Jacob Kaplan-Moss, Django developer

CouchDB’s design borrows heavily from web architecture and the concepts of resources, methods, and representations. It augments this with powerful ways to query, map, combine, and filter your data. Add fault tolerance, extreme scalability, and incremental replication, and CouchDB defines a sweet spot for document databases.

We write software to improve our lives and the lives of others. Usually this involves taking some mundane information—such as contacts, invoices, or receipts—and manipulating it using a computer application. CouchDB is a great fit for common applications like this because it embraces the natural idea of evolving, self-contained documents as the very core of its data model.

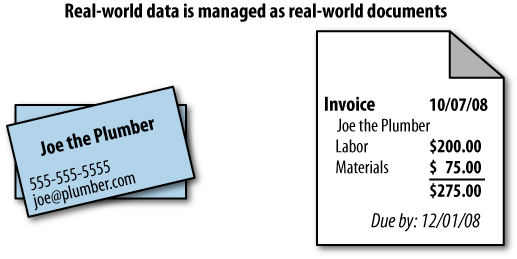

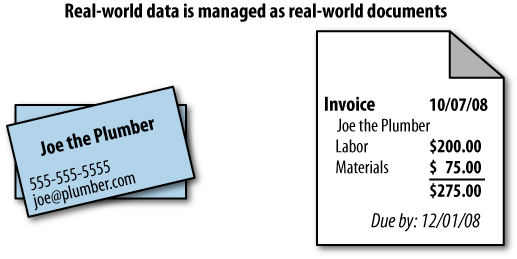

An invoice contains all the pertinent information about a single transaction—the seller, the buyer, the date, and a list of the items or services sold. As shown in Figure 1, “Self-contained documents”, there’s no abstract reference on this piece of paper that points to some other piece of paper with the seller’s name and address. Accountants appreciate the simplicity of having everything in one place. And given the choice, programmers appreciate that, too.

Figure 1. Self-contained documents

Yet using references is exactly how we model our data in a relational database! Each invoice is stored in a table as a row that refers to other rows in other tables—one row for seller information, one for the buyer, one row for each item billed, and more rows still to describe the item details, manufacturer details, and so on and so forth.

This isn’t meant as a detraction of the relational model, which is widely applicable and extremely useful for a number of reasons. Hopefully, though, it illustrates the point that sometimes your model may not “fit” your data in the way it occurs in the real world.

Let’s take a look at the humble contact database to illustrate a different way of modeling data, one that more closely “fits” its real-world counterpart—a pile of business cards. Much like our invoice example, a business card contains all the important information, right there on the cardstock. We call this “self-contained” data, and it’s an important concept in understanding document databases like CouchDB.

Most business cards contain roughly the same information—someone’s identity, an affiliation, and some contact information. While the exact form of this information can vary between business cards, the general information being conveyed remains the same, and we’re easily able to recognize it as a business card. In this sense, we can describe a business card as a real-world document.

Jan’s business card might contain a phone number but no fax number, whereas J. Chris’s business card contains both a phone and a fax number. Jan does not have to make his lack of a fax machine explicit by writing something as ridiculous as “Fax: None” on the business card. Instead, simply omitting a fax number implies that he doesn’t have one.

We can see that real-world documents of the same type, such as business cards, tend to be very similar in semantics—the sort of information they carry—but can vary hugely in syntax, or how that information is structured. As human beings, we’re naturally comfortable dealing with this kind of variation.

While a traditional relational database requires you to model your data up front, CouchDB’s schema-free design unburdens you with a powerful way to aggregate your data after the fact, just like we do with real-world documents. We’ll look in depth at how to design applications with this underlying storage paradigm.

CouchDB is a storage system useful on its own. You can build many applications with the tools CouchDB gives you. But CouchDB is designed with a bigger picture in mind. Its components can be used as building blocks that solve storage problems in slightly different ways for larger and more complex systems.

Whether you need a system that’s crazy fast but isn’t too concerned with reliability (think logging), or one that guarantees storage in two or more physically separated locations for reliability, but you’re willing to take a performance hit, CouchDB lets you build these systems.

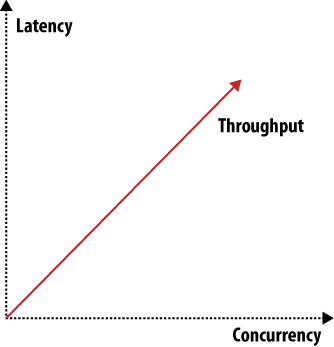

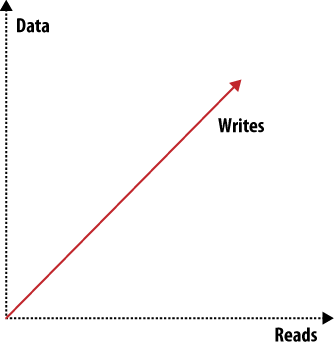

There are a multitude of knobs you could turn to make a system work better in one area, but you’ll affect another area when doing so. One example would be the CAP theorem discussed in the next chapter. To give you an idea of other things that affect storage systems, see Figures 2 and 3.

By reducing latency for a given system (and that is true not only for storage systems), you affect concurrency and throughput capabilities.

Figure 2. Throughput, latency, or concurrency

Figure 3. Scaling: read requests, write requests, or data

When you want to scale out, there are three distinct issues to deal with: scaling read requests, write requests, and data. Orthogonal to all three and to the items shown in Figures 2 and 3 are many more attributes like reliability or simplicity. You can draw many of these graphs that show how different features or attributes pull into different directions and thus shape the system they describe.

CouchDB is very flexible and gives you enough building blocks to create a system shaped to suit your exact problem. That’s not saying that CouchDB can be bent to solve any problem—CouchDB is no silver bullet—but in the area of data storage, it can get you a long way.

CouchDB replication is one of these building blocks. Its fundamental function is to synchronize two or more CouchDB databases. This may sound simple, but the simplicity is key to allowing replication to solve a number of problems: reliably synchronize databases between multiple machines for redundant data storage; distribute data to a cluster of CouchDB instances that share a subset of the total number of requests that hit the cluster (load balancing); and distribute data between physically distant locations, such as one office in New York and another in Tokyo.

CouchDB replication uses the same REST API all clients use. HTTP is ubiquitous and well understood. Replication works incrementally; that is, if during replication anything goes wrong, like dropping your network connection, it will pick up where it left off the next time it runs. It also only transfers data that is needed to synchronize databases.

A core assumption CouchDB makes is that things can go wrong, like network connection troubles, and it is designed for graceful error recovery instead of assuming all will be well. The replication system’s incremental design shows that best. The ideas behind “things that can go wrong” are embodied in the Fallacies of Distributed Computing:

Existing tools often try to hide the fact that there is a network and that any or all of the previous conditions don’t exist for a particular system. This usually results in fatal error scenarios when something finally goes wrong. In contrast, CouchDB doesn’t try to hide the network; it just handles errors gracefully and lets you know when actions on your end are required.

CouchDB takes quite a few lessons learned from the Web, but there is one thing that could be improved about the Web: latency. Whenever you have to wait for an application to respond or a website to render, you almost always wait for a network connection that isn’t as fast as you want it at that point. Waiting a few seconds instead of milliseconds greatly affects user experience and thus user satisfaction.

What do you do when you are offline? This happens all the time—your DSL or cable provider has issues, or your iPhone, G1, or Blackberry has no bars, and no connectivity means no way to get to your data.

CouchDB can solve this scenario as well, and this is where scaling is important again. This time it is scaling down. Imagine CouchDB installed on phones and other mobile devices that can synchronize data with centrally hosted CouchDBs when they are on a network. The synchronization is not bound by user interface constraints like subsecond response times. It is easier to tune for high bandwidth and higher latency than for low bandwidth and very low latency. Mobile applications can then use the local CouchDB to fetch data, and since no remote networking is required for that, latency is low by default.

Can you really use CouchDB on a phone? Erlang, CouchDB’s implementation language has been designed to run on embedded devices magnitudes smaller and less powerful than today’s phones.

The next chapter further explores the distributed nature of CouchDB. We should have given you enough bites to whet your interest. Let’s go!