Figure 1. CouchDB executes application code stored in design documents

CouchDB is useful for many areas of an application. Because of its incremental MapReduce and replication characteristics, it is especially well suited to online interactive document and data management tasks. These are the sort of workloads experienced by the majority of web applications. This coupled with CouchDB’s HTTP interface make it a natural fit for the web.

In this part, we’ll tour a document-oriented web application—a basic blog implementation. As a lowest common denominator, we’ll be using plain old HTML and JavaScript. The lessons learned should apply to Django/Rails/Java-style middleware applications and even to intensive MapReduce data mining tasks. CouchDB’s API is the same, regardless of whether you’re running a small installation or an industrial cluster.

There is no right answer about which application development framework you should use with CouchDB. We’ve seen successful applications in almost every commonly used language and framework. For this example application, we’ll use a two-layer architecture: CouchDB as the data layer and the browser for the user interface. We think this is a viable model for many document-oriented applications, and it makes a great way to teach CouchDB, because we can easily assume that all of you have a browser at hand without having to ensure that you’re familiar with a particular server-side scripting language.

This part is interactive, so be prepared to follow along with your laptop and a running CouchDB database. We’ve made the full example application and all of the source code examples available online, so you’ll start by downloading the current version of the example application and installing it on your CouchDB instance.

A challenge of writing this book and preparing it for production is that CouchDB is evolving at a rapid pace. The basics haven’t changed in a long time, and probably won’t change much in the future, but things around the edges are moving forward rapidly for CouchDB’s 1.0 release.

This book is going to press as CouchDB version 0.10.0 is about to be released. Most of the code was written against 0.9.1 and the development trunk that is becoming version 0.10.0. In this part we’ll work with two other software packages: CouchApp, which is a set of tools for editing and sharing CouchDB application code; and Sofa, the example blog itself.

See http://couchapp.org for the latest information about the CouchApp model.

As a reader, it is your responsibility to use the correct versions of these packages. For CouchApp, the correct version is always the latest. The correct version of Sofa depends on which version of CouchDB you are using. To see which version of CouchDB you are using, run the following command:

curl http://127.0.0.1:5984

You should see something like one of these three examples:

{"couchdb":"Welcome","version":"0.9.1"}

{"couchdb":"Welcome","version":"0.10.0"}

{"couchdb":"Welcome","version":"0.11.0a858744"}

These three correspond to versions 0.9.1, 0.10.0, and trunk. If the version of CouchDB you have installed is 0.9.1 or earlier, you should upgrade to at least 0.10.0, as Sofa makes use of features not present until 0.10.0. There is an older version of Sofa that will work, but this book covers features and APIs that are part of the 0.10.0 release of CouchDB. It’s conceivable that there will be a 0.9.2, 0.10.1 and even a 0.10.2 release by the time you read this. Please use the latest release of whichever version you prefer.

Trunk refers to the latest development version of CouchDB available in the Apache Subversion repository. We recommend that you use a released version of CouchDB, but as developers, we often use trunk. Sofa’s master branch will tend to work on trunk, so if you want to stay on the cutting edge, that’s the way to do it.

If you’re not familiar with JavaScript, we hope the source examples are given with enough context and explanation so that you can keep up. If you are familiar with JavaScript, you’re probably already excited that CouchDB supports view and template rendering JavaScript functions.

One of the advantages of building applications that can be hosted on any standard CouchDB installation is that they are portable via replication. This means your application, if you develop it to be served directly from CouchDB, gets offline mode “for free.” Local data makes a big difference for users in a number of ways we won’t get into here. We call applications that can be hosted from a standard CouchDB CouchApps.

CouchApps are a great vehicle for teaching CouchDB because we don’t need to worry about picking a language or framework; we’ll just work directly with CouchDB so that readers get a quick overview of a familiar application pattern. Once you’ve worked through the example app, you’ll have seen enough to know how to apply CouchDB to your problem domain. If you don’t know much about Ajax development, you’ll learn a little about jQuery as well, and we hope you find the experience relaxing.

Applications are stored as design documents (Figure 1, “CouchDB executes application code stored in design documents”). You can replicate design documents just like everything else in CouchDB. Because design documents can be replicated, whole CouchApps are replicated. CouchApps can be updated via replication, but they are also easily “forked” by the users, who can alter the source code at will.

Figure 1. CouchDB executes application code stored in design documents

Because applications are just a special kind of document, they are easy to edit and share.

J. Chris says: Thinking of peer-based application replication takes me back to my first year of high school, when my friends and I would share little programs between the TI-85 graphing calculators we were required to own. Two calculators could be connected via a small cable and we’d share physics cheat sheets, Hangman, some multi-player text-based adventures, and, at the height of our powers, I believe there may have been a Doom clone running.

The TI-85 programs were in Basic, so everyone was always hacking each other’s hacks. Perhaps the most ridiculous program was a version of Spy Hunter that you controlled with your mind. The idea was that you could influence the pseudorandom number generator by concentrating hard enough, and thereby control the game. Didn’t work. Anyway, the point is that when you give people access to the source code, there’s no telling what might happen.

If people don’t like the aesthetics of your application, they can tweak the CSS. If people don’t like your interface choices, they can improve the HTML. If they want to modify the functionality, they can edit the JavaScript. Taken to the extreme, they may want to completely fork your application for their own purposes. When they show the modified version to their friends and coworkers, and hopefully you, there is a chance that more people may want to make improvements.

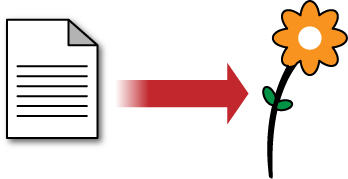

As the original developer, you have the control over your version and can accept or reject changes as you see fit. If someone messes around with the source code for a local application and breaks things beyond repair, they can replicate the original copy from your server, as illustrated in Figure 2, “Replicating application changes to a group of friends”.

Figure 2. Replicating application changes to a group of friends

Of course, this may not be your cup of tea. Don’t worry; you can be as restrictive as you like with CouchDB. You can restrict access to data however you wish, but beware of the opportunities you might be missing. There is a middle ground between open collaboration and restricted access controls.

Once you’ve finished the installation procedure, you’ll be able to see the full application code for Sofa, both in your text editor and as a design document in Futon.

What happens if you add an HTML file as a document attachment? Exactly the same thing. We can serve web pages directly with CouchDB. Of course, we might also need images, stylesheets, or scripts. No problem; just add these resources as document attachments and link to them using relative URIs.

Let’s take a step back. What do we have so far? A way to serve HTML documents and other static files on the Web. That means we can build and serve traditional websites using CouchDB. Fantastic! But isn’t this a little like reinventing the wheel? Well, a very important difference is that we also have a document database sitting in the background. We can talk to this database using the JavaScript served up with our web pages. Now we’re really cooking with gas!

CouchDB’s features are a foundation for building standalone web applications backed by a powerful database. As a proof of concept, look no further than CouchDB’s built-in administrative interface. Futon is a fully functional database management application built using HTML, CSS, and JavaScript. Nothing else. CouchDB and web applications go hand in hand.

There are plenty of examples of CouchApps in the wild. This section includes screenshots of just a few sites and applications that use a standalone CouchDB architecture.

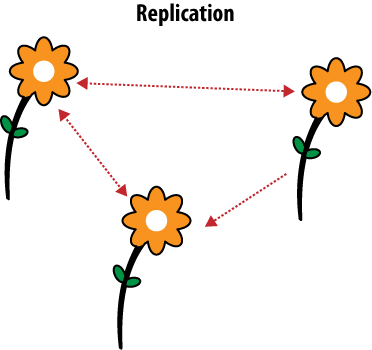

Damien Katz, inventor of CouchDB and writer of this book’s Foreword, decided to see how long it would take to implement a shared calendar with real-time updates as events are changed on the server. It took about an afternoon, thanks to some amazing open source jQuery plug-ins. The calendar demo is still running on J. Chris’s server. See Figure 3, “Group calendar”.

Figure 3. Group calendar

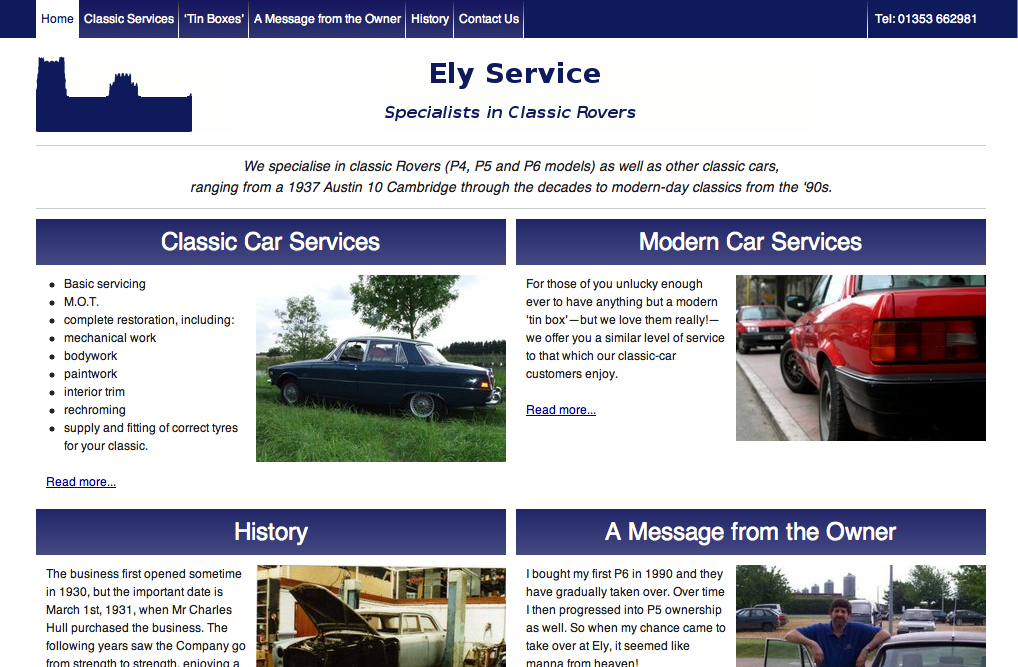

Jason Davies swapped out the backend of the Ely Service website with CouchDB, without changing anything visible to the user. The technical details are covered on his blog. See Figure 4, “Ely Service”.

Figure 4. Ely Service

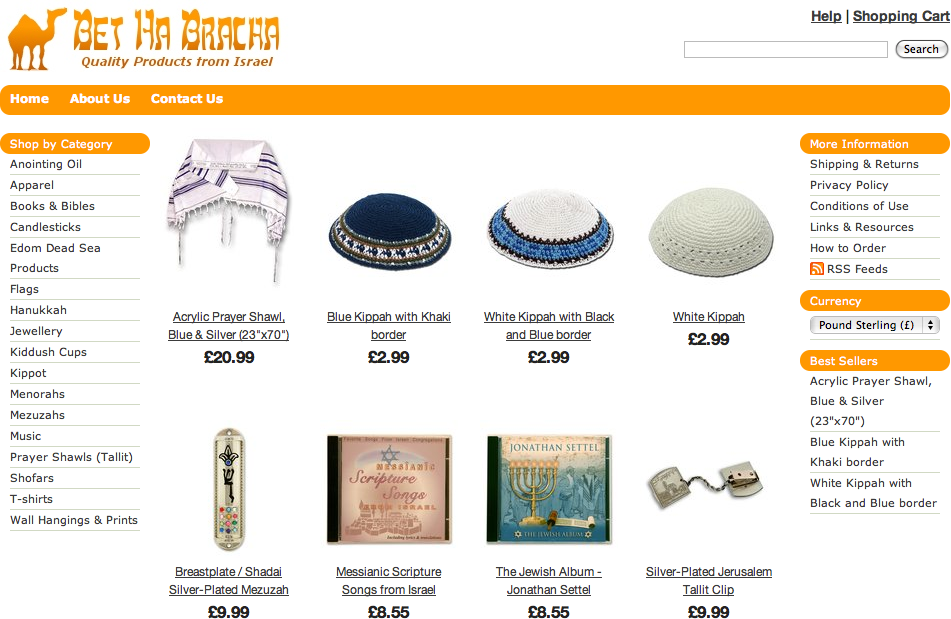

Jason also converted his mom’s ecommerce website, Bet Ha Bracha, to a CouchApp. It uses the _update handler to hook into different transaction gateways. See Figure 5, “Bet Ha Bracha”.

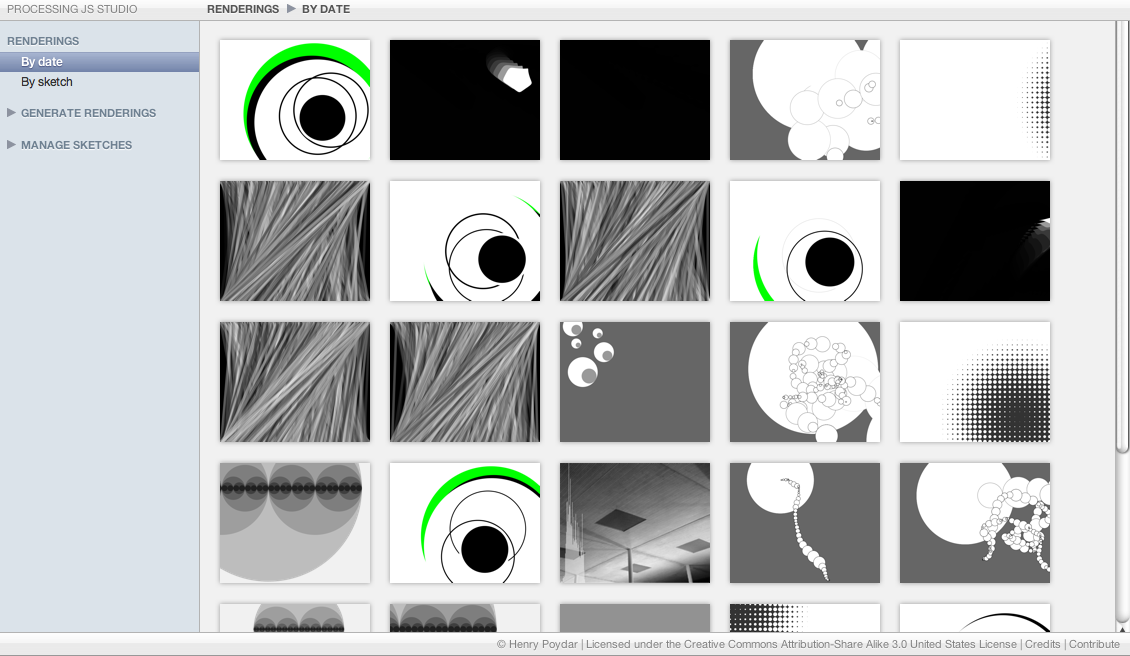

Processing JS is a toolkit for building animated art that runs in the browser. Processing JS Studio is a gallery for Processing JS sketches. See Figure 6, “Processing JS Studio”.

Figure 5. Bet Ha Bracha

Figure 6. Processing JS Studio

Swinger is a CouchApp for building and sharing presentations. It uses the Sammy JavaScript application framework. See Figure 7, “Swinger”.

Figure 7. Swinger

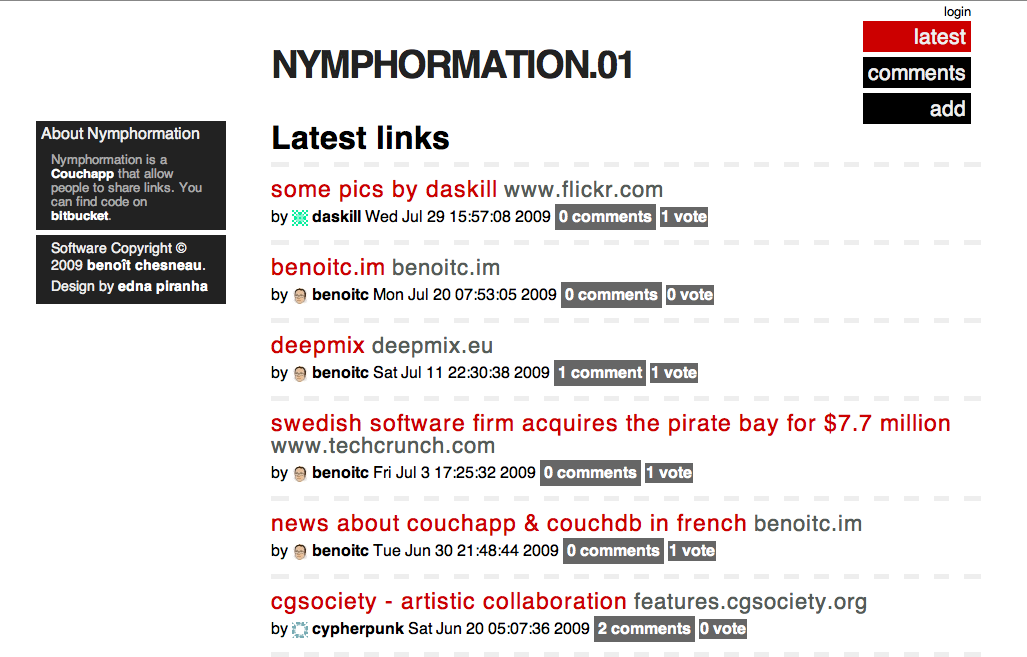

Nymphormation is a link sharing and tagging site by Benoît Chesneau. It uses CouchDB’s cookie authentication and also makes it possible to share links using replication. See Figure 8, “Nymphormation”.

Boom Amazing is a CouchApp by Alexander Lang that allows you to zoom, rotate, and pan around an SVG file, record the different positions, and then replay those for a presentation or something else (from the Boom Amazing README). See Figure 9, “Boom Amazing”.

Figure 8. Nymphormation

Figure 9. Boom Amazing

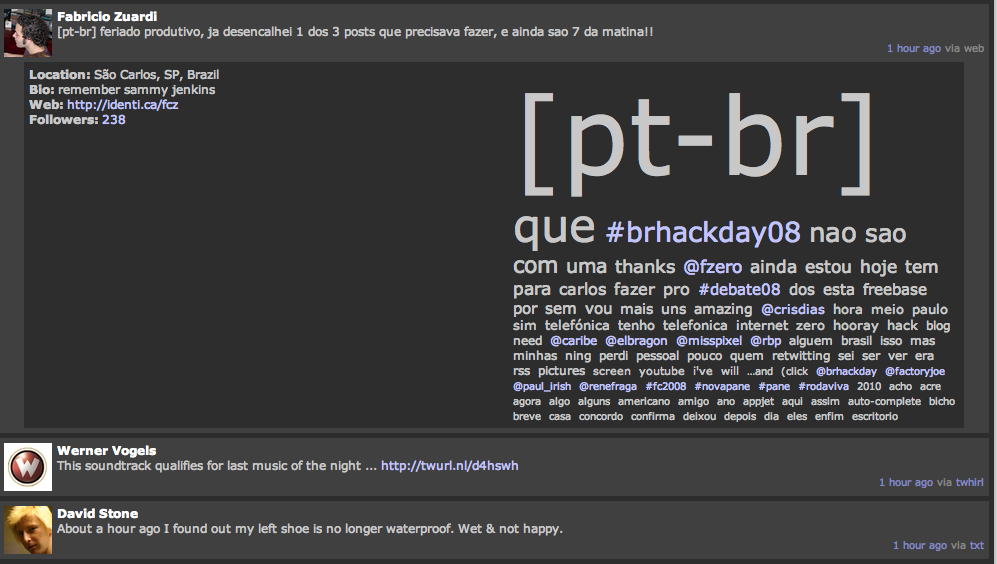

The CouchDB Twitter Client was one of the first standalone CouchApps to be released. It’s documented in J. Chris’s blog post, “My Couch or Yours, Shareable Apps are the Future”. The screenshot in Figure 10, “Twitter Client” shows the word cloud generated from a MapReduce view of CouchDB’s archived tweets. The cloud is normalized against the global view, so universally common words don’t dominate the chart.

Figure 10. Twitter Client

Toast is a chat application that allows users to create channels and then invite others to real-time chat. It was initially a demo of the _changes event loop, but it started to take off as a way to chat. See Figure 11, “Toast”.

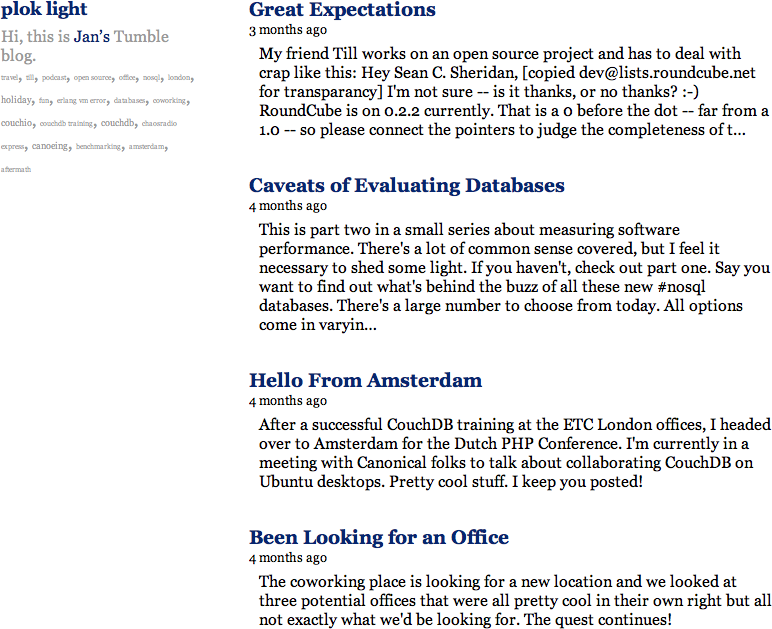

Sofa is the example application for this part, and it has been deployed by a few different authors around the web. The screenshot in Figure 12, “Sofa” is from Jan’s Tumblelog. To see Sofa in action, visit J. Chris’s site, which has been running Sofa since late 2008.

Figure 11. Toast

Figure 12. Sofa

J. Chris decided to port his blog from Ruby on Rails to CouchDB. He started by exporting Rails ActiveRecord objects as JSON documents, paring away some features, and adding others as he converted to HTML and JavaScript.

The resulting blog engine features access-controlled posting, open comments with the possibility of moderation, Atom feeds, Markdown formatting, and a few other little goodies. This book is not about jQuery, so although we use this JavaScript library, we’ll refrain from dwelling on it. Readers familiar with using asynchronous XMLHttpRequest (XHR) should feel right at home with the code. Keep in mind that the figures and code samples in this part omit many of the bookkeeping details.

We will be studying this application and learning how it exercises all the core features of CouchDB. The skills learned in this part should be broadly applicable to any CouchDB application domain, whether you intend to build a self-hosted CouchApp or not.